Cinema Sark, John Wallace

photo, James Wyness

Borderlands: The Historical and Cultural Significance of the Anglo-Scottish Border

13 December 2013, Gallery North, Northumbria University.

Convened by Dr Ysanne Holt (Northumbria University) and Dr Angela McClanahan (Edinburgh College of Art)

On 13 December Claire, Jules and I attended ‘Close Friends’, the first in an ESRC seminar series hosted by Northumbria University on the theme of assessing the impact of greater Scottish autonomy on the North of England. The programme can be consulted here and an account by our close friends in Dumfries and Galloway, who spoke at the seminar, can be read here

My impression of the event was that it offered a forum for meaningful and incisive discussion on a range of topics that are not easily covered by those representations of debates (dressed up as real debates) which take place in television studios. Nor are such meaningful discussions likely to happen in the village and town halls of the Borders. This was yet another excellent opportunity, following the series of discussion events hosted by the Environmental Arts Festival Scotland in the autumn of 2013, to listen to a range of speakers covering topics of critical importance to the margins, edges, centres and borderlines in, around and between the counties of Southern Scotland and the shires of Northern England. The complexity of cultural, social and economic relationships between the regions was aptly described as a set of superimposed Venn diagrams, not dissimilar to a living ecosystem.

Without echoing too much what has been said in The Commonty (above), we learned that the whole notion of ‘North’ is up for fresh discussion in the light of moves towards Scottish independence. Regardless of the referendum result, preparations, both practical and intellectual, will have to be made by those regions adjoining Scotland. Both Northumberland and Cumbria might very soon, in the face of possible Scottish independence or at least a process of moving towards greater autonomy, find itself on the extreme Northern fringes of a different England, itself independent of Scotland. And paradoxically or if you prefer, reasonably, professionals are looking with great interest at topics of mutual interest to regions on either side of the borderline: land use and (crucially) food production, tourism, transport, cultural strategies, not to mention differing policies, attitudes and initiatives relating to health and education. In addition Northumberland and Cumbria might themselves be forced into a new East/West dialogue, again looking at areas of mutual interest in the wake of their (possible) increasing isolation from London following the production of new abstract spaces along the border.

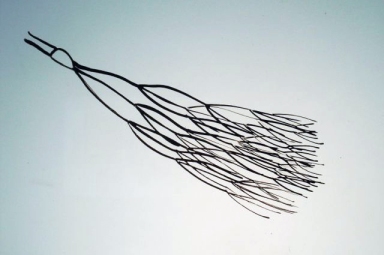

As a discussion around the arts and individual arts projects we were treated to illustrated accounts of projects from Dumfries and Galloway (John Wallace’s Cinema Sark, shown in the image above), North Northumberland (Northumbrian Exchanges) and the ghost town of Riccarton near Hawick. There is a long and deeply embedded tradition of cross-border cultural merging and collaboration, a well-oiled machinery of processes and institutional methodologies that are set to grow and develop over time in spite of national political changes. There is no University of the Borders which represents the needs of the creative and cultural community on the Scottish side – any notion of advocacy or mediation on the part of Edinburgh or Glasgow is fanciful. It would therefore be apposite (and again wonderfully paradoxical) to look to institutions like Northumbria University for such advocacy and mediation, not only because they have already begun the work of cross-border collaboration, but more importantly because doing so subverts the notion of border as a produced space implying exclusion, exclusivity and divisiveness.

Any discussion of Borders and Borderlands is of great interest to projects like Working the Tweed, for obvious reasons relating to the topography and political geography of the river, less obviously perhaps in view of the fact that Scotland’s Land Use Strategy is currently being piloted in the Scottish Borders and Aberdeenshire. The Borders pilot, in adopting an ecosystem approach, will be considering the following:-

•Provisioning services: e.g. food, fibre

•Regulating services: e.g. water quality, soil carbon

•Supporting services: e.g. biodiversity

•Cultural services: e.g. recreation, sense of place pilot looking at cultural strategy as a subset of the main heading.

While all of these areas are of interest to artists like ourselves engaged with a working river, the last field of investigation sits especially well alongside many of the key points discussed at the seminar. This study will undoubtedly be met with great enthusiasm by the ‘cultural sector’, which includes artists and arts administrators working in the region, but the initiative also carries the potential to encourage new perceptions among the wider community of scientists, educators, landowners, food producers and, hopefully, politicians. We look forward with to Northumbria University’s proposed conference in 2014.

James Wyness