Leah Gibbs (LG), Human Geographer at the University of Wollongong, Australia, in conversation with Working the Tweed artists, Kate Foster (KF) and Claire Pençak (CP).

Introduction

In the project Working the Tweed, we set out to work with different kinds of specialist knowledge. This yields various ways to think about the Tweed Catchment, and make different artistic connections and new kinds of maps. We are thinking through what we, as artists, might offer in engaging with projects that deal with sustainable land-use and the realities of environmental change. We are delighted to be able to converse with Leah Gibbs, a human geographer at the University of Wollongong, whose work concerns the cultures and politics of water. Leah has considerable experience of multi-disciplinary work focussing on land management. She explains her concept of ‘passing-through places’. This overlaps with Kate Foster’s ideas of documenting ‘so-far stories’, and Claire Pençak’s thinking on improvisation as a way to investigate relationship to place through movement.

Conversation

KF: Leah, you have written about ‘passing-through places’, which is an intriguing idea and keeps coming to mind as we plan the Working the Tweed project. Can you explain why you find the concept of ‘passing through’ helpful, and how you came to adopt the term?

LG: The idea of a ‘passing-through place’ emerged from a project I’ve been involved with over the last few years called ‘SiteWorks’. SiteWorks is an ongoing series of collaborative projects, which was initiated by arts organisation Bundanon Trust, and is based on the Shoalhaven River, just south of where I live in Wollongong (south eastern Australia). It involves a really interesting, shifting group of people: arts practitioners, scientists, other scholars, local people, including folk involved in Landcare groups, and other local organisations. The project asks participants to respond to the Bundanon sites on the river. I was thrilled to be invited to be part of it in 2010.

Image 1: Looking down the Shoalhaven River from Bundanon property ‘Riversdale’, August 2010.

Photo © Leah Gibbs 2010.

As a Human Geographer, I’m really interested in people and place, so when I first visited Bundanon I was keen to learn about people’s relationships with the site, and also how an arts-science collaboration might help us to understand place. I quickly learned that Bundanon is important to a lot of people. But it’s a place that people tend to pass through: visitors to the site, school groups, artists in residence, Bundanon employees, all pass through this place. We learn, and make connections, but we don’t dwell here. The previous owners of Bundanon were the late Australian artist Arthur Boyd and his family. Bundanon shaped a large body of Boyd’s work, and the place is strongly associated with him. But he and his family lived here for a relatively short time. Learning from the archive, it seems earlier settler families also passed through this place.

There has been some recent work done on the Indigenous heritage and history of the Bundanon properties, and this work finds that the main population centre prior to European colonisation was downstream, near the estuary. But the site was still important: people passed through here, often travelling on the river, to get to food and hunting sites, and to ceremony sites.

So what I’m trying to get at with the idea of a ‘passing-through place’ is that some places may not be permanently dwelt in, but are extremely significant, vital places none-the-less. Permanent dwelling, fixity, longevity, are not the only ways of forming meaningful relationships with places.

Image 2: Across the floodplain, March 2011. Photo © Leah Gibbs 2011.

In addition, in Australia – as in other parts of the world – the idea of ‘belonging’ is highly political. It feeds into thinking about ‘native’ and ‘introduced’, ‘invasive’ or ‘feral’ species of plants and animals, and it goes on to inform management and decision-making about these things. Ideas about belonging also influence thinking and action towards people, particularly in the context of indigenous relations, ethnicity and migration. But belonging is highly complex in a settler-dominated society. Concepts of belonging that are based on fixed notions of permanence or longevity in a place can lead to some very troublesome, racist attitudes and even policy.

So I like the concept of a ‘passing-through place’ for a couple of reasons. First because it highlights the significance of places that may not be permanently dwelt in, but are vital none-the-less; and second, because it unsettles fixed notions of belonging. And it strikes me that challenging fixed ideas of belonging is incredibly important in the context of contemporary environmental change. It’s in this context that we need to learn how to better live with other humans and a more-than-human world under changing conditions.

I’ve written more extensively about the idea of a ‘passing-through place’ and my experiences as a SiteWorks participant in a recent article published in the journal ‘Cultural Geographies’.

KF: What you have said shows how ‘unsettling’ a fixed idea can be a constructive step to take. I am wary when I hear ‘The Story of X, Y, Z’ – all in capitals. Intellectually we might know that many different stories can be told but they do still jostle for position. We seem to shy away from complexity. Happy-endings can appeal – but for whom, where, and in what timescale?

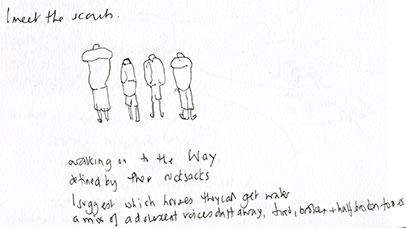

I used a prompt from political ecology to work out how making ‘so-far stories’ can expand my human viewpoint. I borrowed this from the work of geographer Doreen Massey who asks us to think of landscape as an event, as a simultaneity of ‘stories-so-far’. This is a sketchbook extract, written when drawing a thistle being blown in the wind.

Image 3: sketchbook extract © Kate Foster 2011

I know that geographical theory takes time and work to absorb, and believe that a rigorous and self-disciplined approach, learning from shared experience, is important. The idea of simultaneity (at different timescales) by-passes anthropocentrism. I set out artistically to attaining ‘ecocentrism’ but I am re-thinking this. I realise that learning about human environmental impact – and degradation – has also taught me more about what it is to be human. This is what I wrote in that article:

Unfinishable as they are, so-far stories may afford possibilities and juxtapositions that escape an aesthetic of despair. Of course the prompt might be anguish or anger, but fury and grief should not overwhelm quieter voices and tender ways of working, in order to acknowledge complexity.

KF: Claire, can you say more about how you use movement improvisation to explore place? Perhaps it’s best to be there with you to find out for ourselves! Does it help to document this kind of exploration? If so, how?

CP: There are several things here.

There is movement improvisation as a way of working that encourages an open, responsive and playful approach and doesn’t require that you follow a series of set steps. There is also the dancer whose body is a passing through place, a transformative place and place of flux. And there is the witness.

For me improvisation encourages thinking on your feet. It is about responding to and being in relationship to – a person or a place or an object or an idea – at a given time, season and place.

It is a process towards finding ways to traverse, to move around, over, under and through that might offer opportunities to be in a slightly different relationship to place. By not having to follow proscribed procedures and pathways it permits us to wander off the beaten track.

This way of working could suggest other ways to understand what place might or could be. It would certainly suggest that place is neither static nor singular but is in a state of becoming and is shaped by the interactions that take place there. If the dancer shifts – does the place not shift too?

For me this is a performative relationship.

Dancers are trained for years to literally place themselves and also to traverse, to pass through.

A dancer brings a different way of paying attention, an under_standing* that is corporeal, terrestrial and aerial. Flux is where they are most at home.

Improvisation isn’t really something to be captured through documentation – it can be experienced, recalled and discussed but doesn’t take well to being fixed as it is thinking in action. The body ‘thinking’ through action.

It can though stimulate images, dialogue, writing.

I like the idea of a companion or witness, as their presence brings a creative eye to the process.

Improvisation is not a spectator sport but collaboration. The witness is there to look closely. They bring their eyes and ears and their presence. They are viewing points and can chose to shift their point of view and their focus of attention and so contribute to the improvisation.

The documentation lies somewhere in the dialogue between the dancer and the witness.

Image 4: Participants at Working the Tweed Riverside Meeting, August 2013. We were looking under a bridge to find traces of otters using the river and marking territory. Photo © Kate Foster 2013.

This conversation has begun to show how human geography, visual art and dance can interweave. Having glimpsed the insights that geographers can offer, our next discussion will be about why ‘more-than-human’ might be a helpful term that expands on traditional ideas of Nature.

References

• http://smah.uow.edu.au/sees/eesstaff/UOW080115.html

• http://www.bundanon.com.au/siteworks

• http://www.bundanon.com.au/

• http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/05/17/1474474013487484.abstract

• Gibbs L In Press Arts-science collaboration, embodied research methods, and the politics of belonging: ‘SiteWorks’ and the Shoalhaven River, Australia. cultural geographies doi: 10.1177/1474474013487484 (published online 17 May 2013).

• Massey, D. 2006. ‘Landscapes as a Provocation: reflections on moving mountains. Journal of Material Culture, 11(1-2), pp. 33–48.

• http://www.politicalecology.org/2012/01/responses-where-is-politics-in.html

Footnote

* When Claire Pençak speaks about under_standing, she gives it a certain emphasis. Translated into text, using the underscore intends to convey the idea that we stand from underneath – that standing is ‘feet up knowledge’.

Rights: Text © authors, Leah Gibbs, Claire Pençak, Kate Foster, unless otherwise stated. Images credited individually.